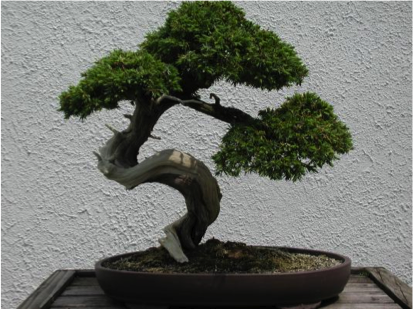

Just in case you didn’t know, a

Bonsai is an ornamental tree or shrub grown in a pot and artificially prevented

from reaching its normal size. While writing his poem “Bonsai,” Billy Collins

had obviously been staring intently across the room he was in at his own

miniature tree. The first thing he says, is how only one Bonsai can “Throw a

room completely out of whack.” It’s so small, so it makes everything around it

look gigantic; oversized. He makes it seem as if it has its own world, as he

does in many other of his poems. “A lone stark gesture of wood on the distant

cliff of a table.” He then goes on to explain that when looked at up close, the

Bonsai draws everything down to its size; “The box of matches is a raft, and

the coffee cup a cistern..” Billy Collins obviously let his imagination run

wild with this poem, describing his own little world by looking at a simple

Bonsai tree. He explains how he wants to climb up into its tiny branches and

look down and see a “tiny whale.. Plunging forward through the troughs.” To

make the poet see everything pulled down to proportion with the Bonsai tree,

Collins ingeniously makes every stanza only two lines long, nice and neat; just

like a Bonsai Tree.

Read as we discuss the poetry of poet laureate Billy Collins from his collection 'Taking off Emily Dickinson's Clothes.' We are A-level literature students from Braeburn School Arusha, Tanzania (in Africa) and welcome constructive discussion and viewpoints.

Tuesday, 23 September 2014

Billy Collins And All That Jazz: An Essay by J.Doria

You can’t read

Billy Collins’ poems without considering their background music, which, like

his comic and physically impaired mice, perforates his words and timbre of his poetry, a distant

accompaniment, a soundtrack to his verses. The central focus here will be Many Faces of Jazz from Picnic, Lightning with reference to some

other works from Questions of Angels,

The Apple that Astonished Paris and The Art of Drowning.

Billy Collins has

said that he likes to be alone with his reader, creating a very personal and intimate

link between ourselves and the poet. Reading is a singular act and Collins

makes full advantage of this. Not only does he seduce the reader by his

profoundly simple yet enchanting verse, he shares his love of music as well,

almost gifting us with a mixed tape ranging from classical to jazz to the blues

to a track on the radio. In this poem, The

Many Faces of Jazz, Collins reflects on our complicated relationship with

this genre of music which he clearly loves “and, most essential, the whole/head

furiously,/ yet almost imperceptibly nodding/ in total and absolute agreement.”

The poem takes

you into a smoky, hazy jazz bar perhaps by invitation where we watch an

audience. Jazz can be a musical estrangement of sorts. It jars. Tempos can be

jagged and ragged. It refuses to soar with Beethovian swells, climaxing

gloriously and unforgivingly. We feel we should ‘understand’ it but don’t. One

almost feels uneducated. Perhaps it is this which makes us feel uncomfortable

or the liberty which improvisation offers. Why can’t a tune be a tune, for

godsakes, you might ask? There’s almost too much freedom and interpretation to

it. It’s persistent in its clashing and gnashing of teeth. It titillates and

teases but fails, for some, in allowing a comfort zone, a final ‘aha’ moment,

with which Bach is littered or Vivaldi or, she blushingly confesses, Abba. Chords

don’t melt into each other like puzzle pieces; they dive and soar and race and

pause all over the place like a drunken spider, like confetti in the wind. It

free flows. One must confess, it’s challenging and mostly one feels out of one’s

depth.

It is precisely

this estrangement which Collins manages to express in his poem The Many Faces of Jazz. We take delight

in realizing we are not alone in our “pained concentration” and that indeed, we

have unwittingly chosen this “new source of agony” whether we like it or not. It

is noted that the person with a look of “existential bemusement” cannot be

ruffled by this musical flow of improvisation, or marginally impressed, denoted

by his “lifted” eyebrows and the casual “oscillating” swizzle stick held

nonchalantly in his free hand. One imagines a stern whisky in the other.

We glance over to

the uber cool girl in the academic

and softly alluring turtle necked sweater, her head a swooning “flower on a

stem”, her “lips slightly parted” in a seductive stance, perhaps hoping for the

attention of some other like minded jazz enthusiast and we wish we were younger

and prettier. For some reason, the other faces are staunchly male. We cannot

imagine a man being a “langorous droop” over a ballad as this perhaps

mistakenly remains in the realms of female, born out of a terrible and innately

sexist prejudice. Our suspicions are confirmed by the possessive article of

“her half closed eyes” as she basks under our jealous gaze.

The music distracts

us and we turn our heads and see the “fellow at the front table” who has a

penchant for “everything but the instrument” which leaves the vocals, we

conclude, and if something is not done, he will mount the stage and change the

status quo, so great is his passion and need. The “crazy-man-crazy face”

individual cares for nothing but percussion, as any percussionist knows. They demand

attention and take over the sound. A percussionist who listens is a rare find.

This “crazy” owes his raison d’etre

to the drum solo. Nothing else matters to him. Even the person who has some

buried anger within, “locates the body of cold rage dammed up behind the

playing” and loses himself “deeply” almost therapeutically, to it.

Collins then, in

the final stanza, manages to draw our attention back to our round metaphoric

table in the corner of the bar, back to himself. We are by now wondering what his jazz face is although we are already

persuaded that he likes this music. At the same time, we wonder what our jazz

face is “and don’t tell me you don’t have one”. He won’t let us off easily. He

professes his unwavering adoration of the genre by his “furiously, yet almost

imperceptibly nodding” head in “total and absolute agreement.”

Because of our

adoration of the poet, we cannot help ourselves but follow his lead. We are

charmed by Art Blakey’s haphazard and jarring version of Three Blind Mice as

Collins chops parsley in his kitchen and is endearingly affected by “the

thought of them without eyes / and now without tails to trail through the moist

grass” so charmingly described in I Chop

Some Parsley While Listening to Art Blakey’s Version of Three Blind Mice.

He eases us from jazz to the blues, blaming Freddie Hubbard’s “mournful trumpet”

on Blue Moon (or the onions) for “the

wet stinging in my eyes.”

We are driven to listen

to Thelonious Monk tinkling out Ruby My Dear

and imagine “the snow that is coming down this morning” and “how the notes

and the spaces accompany/ its easy falling…as if he had imagined a winter

scene/as he sat at his piano/late one night at the Five Spot” (Snow from Picnic, Lightning). He doesn’t stop there but offers us “an adagio

for strings”, probably a Bach’s cello concerto, “the best of the Ronettes,/ or

George Thorogood and the Destroyers” in one giant and determined musical leap.

Here Collins outlines his uncanny knack of demonstrating how music inextricably

colours the nature of things, not dissimilar to his poetry, particularly.

In Lines Lost Among Trees Collins

beautifully sketches the moment when inspiration flies beyond grasp and blames

it woefully on “ the jazz of timing.”

We cannot have

but sympathy for the poet enduring the incessant barking of a neighbour’s dog

who, in the end, triumphs over an entire orchestra, and Beethoven, in Another Reason Why I Don’t Keep A Gun In The

House. The effusive repetition of “barking, barking, barking” intertwined

with “while the other musicians listen in respectful silence to the famous

barking dog solo”, effectively transmits the insufferable intrusive sound of

the dog barking. Its triumph over an entire orchestra is so outstanding that we

are forced to bow to its canine vocal aptitude.

Collins doesn’t

stop there. All these musical references open up worlds for his lone reader, a

swirling whirlwind of poetry and music. He tells us how The Sensational

Nightingales who, on a Sunday morning “must be credited with the bumping up /

of my spirit, the arousal of mice within…” In Tuesday, June 4, 1991 he figures he “will make him (the house

painter) a tape when he goes back to his brushes and pails” because the painter

“likes this slow rendition / of You Don’t

Know What Love Is.”

Collins’ musical

allegiance takes real shape in The Blues

when he astutely reminds us that “no one takes an immediate interest in the

pain of others…But if you sing it again / with the help of a band / … people

will not only listen,/ they will shift to the sympathetic / edges of their

chairs.” He underscores a human trait. We turn to music and poetry in times of

need and pain in an attempt to define and assuage them.

Perhaps the most touching

of all is Questions About Angels

where he so poignantly ends spiritual, yet unquestionably lyrical, musings on

the life of angels with the unavoidably alluring image of “one female angel

dancing alone in her stocking feet, / a small jazz combo working in the

background./ She sways like a branch in the wind, her beautiful/ eyes closed

and the tall thin bassist leans over / to glance at his watch because she has

been dancing forever, and now it is very late / even for musicians.”

As the bard so

aptly wrote in Twelfth Night, “If

music be the food of love, play on.”

And Mr Collins

certainly, evocatively and profoundly does.

Contemplations on well known nursery rhymes

You know that feeling when you

say a word so often that it sounds weird? Or when you think about something as

simple as ‘Why am I in this room?’ for so long that you start to doubt whether

you really exist? I do, and so does Billy Collins. In his contemplative poem 'I Chop Some Parsley While listening to Art Blakey's version of 'Three Blind Mice'' from his poetic collection ‘Picnic, Lightning’ this is exactly what he

describes.

While he stands in the kitchen

preparing a meal of which the only known ingredients are onions and parsley and

listens to jazz he starts to think about why our well known nursery rhymes tell

stories of pain and emotional turmoil for the little mammals. He says he ‘started

to wonder how they came to be blind.’ This is in the first line of the poem

(which also cunningly just runs on from the title) as a reader you would

immediately be captivated. Finally! Someone who understands the questions you

have been asking yourself as you sang this very nursery rhyme to the little

kids in kindergarten.

The whole poem seems to be a

stream of consciousness. Every line is just running on from the previous stanza

as the narrator starts to feel emotional about these poor little mice ‘without

tails to trail through the moist grass [...].’ This flow of emotions is

emphasised by the fact that it seems to be that the poet has tried to organise

the poem into stanzas, however despite his attempt to keep calm he can’t keep

the lines in the right place, he just

lets them go on and over into the next stanza instead of trying to tame them to

fit them into the stanza they were supposed

to be in. This adds to the reader’s empathy for the narrator. The shape of the

poem on the page is almost crazily disorganised too: the lines are all uneven

lengths, some as short as two words (‘If not,’). It’s almost as if the whole

poem is just a thought that came to the poets mind as he was cooking and

decided it absolutely must be written down that instance. This is a

characteristic of Billy Collins’ poems, in fact the poet himself even said in

an interview that he never spent more than half an hour writing a poem, and

oftentimes doesn’t read through it afterwards either.

The intense imagery that Collins

uses to describe what he thinks could have possibly happened to the poor little

blind mice is also quite heart wrenching: ‘[W]as it a common accident, all

three caught in a searing explosion, a firework perhaps?’ His use of the word ‘searing’

makes a reader flinch because you associate it to times when you perhaps

accidentally touched a hot pan and pulled away, you start to imagine how it

would feel if you didn’t pull your hand away, and start to look deeper into the

sad nursery rhyme. He also uses strong emotion to show how the narrator is

split into two parts – the cynic and the rest of him. The cynic, after having

listened to the story of how the mice came to be blind, tries to walk away to ‘hide

the rising softness he feels inside him.’ It is as though this simple tale made

him emotional and embarrassed because of this unexpected emotion. A reader

would probably feel the same way. After having read the poem I started to also

feel uncomfortable and saddened at the thought of these poor little blind mice ‘without

eyes and now without tails,’ but this is an odd thing to feel sad about so I

too would hide it. The other part of the poet, the non-cynical part that doesn’t

accept this cruelty onto the mice, also shows signs of desperation to hide the

sadness felt after thinking about their fate. He says the onion he is now

cutting ‘might account for the stinging in [his] own eyes.’

All in all, I think this is a

wonderfully thought-provoking poem. After reading it I felt almost relieved

that someone actually bothered to write about something as seemingly trivial as

the lyrics to ‘Three Blind Mice.’ I can’t say that I was happy after reading

about what their possible story could be, but I definitely thoroughly enjoyed

the poem.

Oh also - Here is an awesome picture of Art Blakey:

Marginalia

As the book travels through life, picking up notes and spills and tear

stains, it becomes a way for the reader to communicate with not only the

thoughts of the author, but with all the things left behind by those other

readers.

A Modest Proposal,

mentioned in stanza 3, is a satirical essay from 1729, where Jonathan Swift

suggests that the Irish eat their own children. Collins adds his sarcasm and

humor by adding "Another notes the presence of 'Irony' fifty times outside

the paragraphs of A Modest Proposal.”

Collins' line "'Absolutely,' they shout to Duns Scotus and James Baldwin,' is a reference to the two authors. Duns Scotus was a philosopher in the high middle ages, and James Baldwin was an author who primarily focused on racism in the 1920's.

He is using the shore (in stanza 3) as the edges of the

paper or the margins much as how you would see when you go to the beach. The

reference to the shore provides imagery of hundreds of peoples footprints all

around, but disappear once the water touches the shore.

‘Yet the one I think

of most often,

The one that dangles

from me like a locket,

Was written in the

copy of Catcher in the Rye

I borrowed from the

local library

One slow, hot summer.’

The speaker here recalls his

favorite annotation, a margin note in J.D. Sallinger’s A Catcher in the Rye (1951).He describes his memory of reading the annotation through the simile of a “locket,” like a precious treasure.

‘A few greasy looking smears

And next to them, written in soft pencil-

By a beautiful girl, I could tell,

Whom I would never meet-

‘Pardon the egg salad stains, but I’m in love.’

The poem climaxes with a description of a marginal note that the speaker remembers in a library book, and that he imagines was written by a beautiful girl.

On the other hand, it’s possible that the note referred to some real-life person the girl was in love with. Whether it’s two lovers brought together through a favorite book or a love affair between reader and character, it’s also a metaphor for the love of reading more broadly.

After reading over the poem again I realized that we do the same thing in school. I jot down what comes to my head on the margins of the book, writing what I think is the meaning of the sentence or the metaphor or whatever comes up. The next person who gets my book will be lucky enough to read my ideas and know why I came up with them.

Monday, 22 September 2014

Afternoon with Irish cows.

'Poets are just people who

have read poetry and been moved by that poetry to emulation. Poetry is inspired

by reading poetry,' by Billy Collins.

Afternoon with Irish cows

is a poem about cows, how cows would be 'anchored there on all fours,' or how

cows seem 'patient and dumbfounded.' But is it just about cows? On this post I

will be discussing on the profound meaning of this plain but as you'll see unique

poem.

The poem's structure is seven

lines per stanza and there are five stanzas. Billy Collin's rhythm varies from

line to line, but all first lines of every stanza have a corresponding sequence

of beats. All first lines have more than ten beats compared to the following

lines in each stanza. You also get the tone of the poem from the structure and

use of the letter 'I.' For example in stanza three line 2,' would let out a

sound so phenomenal, that I would put down the paper.' Where you would normally

expect 'I' to start the following line Collins however en jambs it and starts

with 'that.' This has been continuously done through the poem, in stanza one

line four- five, also in the last line of stanza four and the first line of

stanza five. By doing so it makes it hard for the reader to fluently read the

poem, you see the attempt from Collin's to slow the reader. Furthermore

Collin's slows the reader down through the description of the cows, one would

just say ' the cow went moo.' Billy Collins however uniquely slows the reader

down by saying,' bellowing head laboring upward as she gave voice to the rising

full-bodied cry ....announcing the large unadultared cowness of herself.'(stanza

four and five) Billy Collins is already establishing why he is a distinguished

poet laureate in just the structure of this poem.

My first reading of an

'Afternoon with Irish cows,' seemed as a plaintive poem that's talking about

nothing more than cows. But after a number of readings I saw a connection

between 'Afternoon with Irish cows,' and my school. Well first since it's

talking about cows -Irish cows, I decided to find out what's so unique about

Irish cows. In my endeavor to find out what makes the Irish cow so unique I ran

across the Irish moiled cow(which I believe Billy Collins refers to.) The cows

are only set apart from fellow cows with how physically similar they look, they

all have the same black and white color.

So

why did I liken Irish cows to my fellow students? I thought of how interested

Billy Collin's observed the cows and then decided to overlook lines that

directly pointed to Irish cows. What I was left with is the image of a teacher

standing by the window most likely during a lunch break and just being utterly

amazed by how 'mysterious, how patient and dumbfounded they long appear in the

quiet afternoon.' Students just like cows (seems a bit wrong to say) all look

the same, in my school they all dressed in their white tops and navy blue bottoms. Am sure if you ask a teacher they would

sometimes tell you that once in a while they have ' put down the paper or the

knife they were cutting an apple with and walked across' to see why a student

made such a cry, as if they were 'being torched or pierced through the side

with a long spear.' The teachers would confirm that 'it sounded like pain until

they could see the noisy one...that she was only announcing the large unadulterated

cowness of herself.' To add on, sometimes the teachers are surprised that they

'would pass a window and look out to see the field suddenly empty as if

they(the students) had taken wing, flown off to another country.' This is my

view that came to me when reading an 'afternoon with Irish cows' as I watched

my fellow students play/socialize outside. Conclusively, I am sincerely sorry

to comparing my fellow students to cows but then if this will make matters any

better I too will be a cow.

Shoveling Snow with Buddha

Shoveling Snow with Buddha by Billy Collins in his

poem collection ‘Picnic, Lightning’ might be, at first glance, about a man

shoveling snow with Buddha. But through Collins’ humor and wit, we discover it

is about a different subject matter, more prominent than we realize. Indeed, the

action of shoveling snow out of the driveway is practicing religion itself. The

determination “Buddha keeps on shoveling” and the will “purpose of existence”

portrayed are reflective of the power of faith in any religion. To add to that,

the fact that Billy Collins chose to humanize a God such as Buddha is a tool to

get the reader an accessibility to the divine that is often deprived from him

in religious works; he could perhaps be the man shoveling snow with his God.

Furthermore, Buddha seems to be portrayed as a well-respected being that is

humble “All morning long we work side by side”. At last, the poem is suggesting

that the goal of Buddhism is enlightenment, for the narrator truly feels illuminated

by shoveling snow.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)